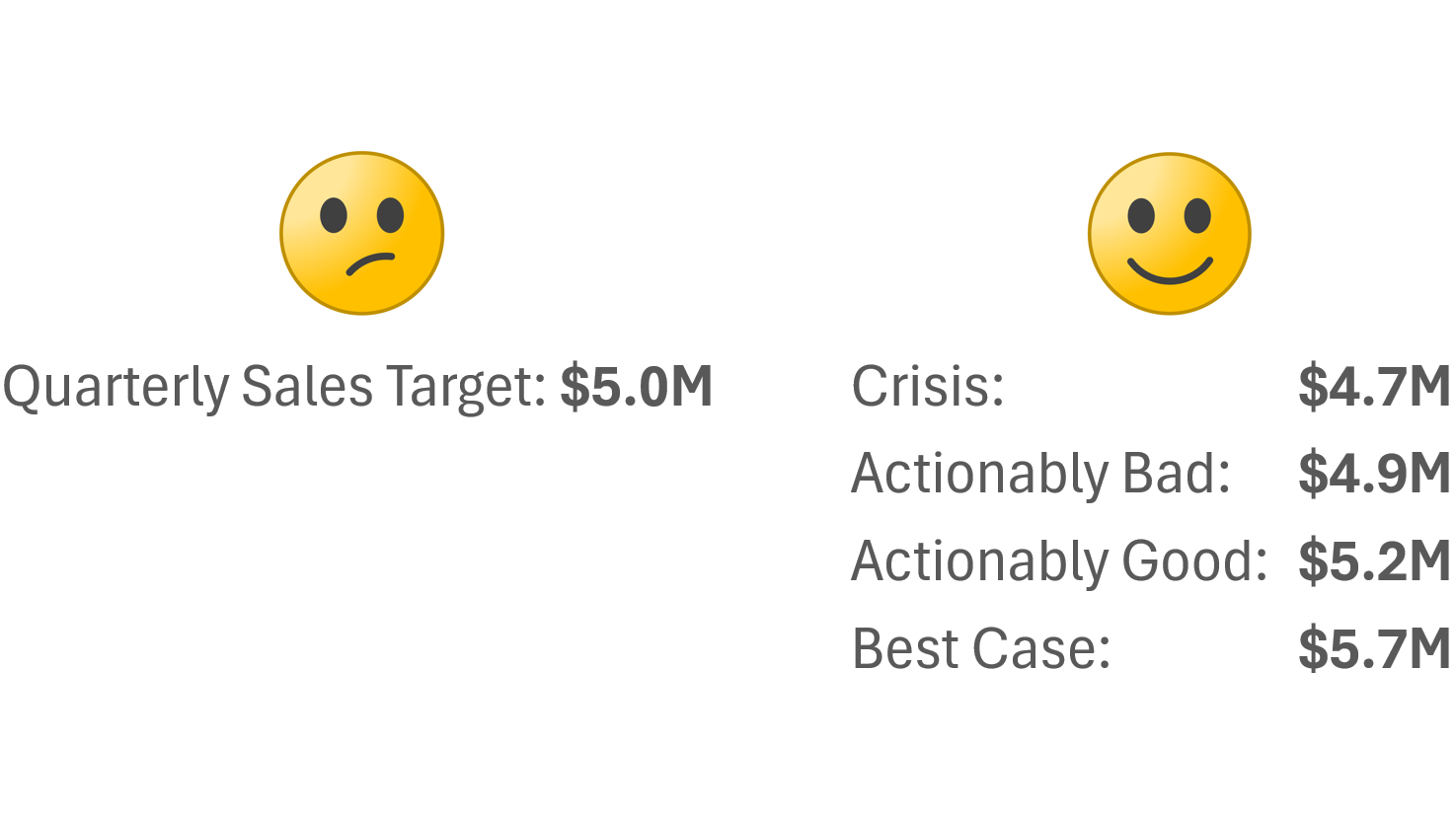

tl;dr: Almost all organizations set single-number targets for their KPIs (e.g., a sales target of $5M for next quarter), however, this approach causes some surprisingly serious problems, all of which are solved by using four numbers to communicate expectations regarding a KPI’s performance, rather than just one.

When I teach my Practical Dashboards course, I recommend against setting single-number targets for KPIs.

I know.

WTF.

Almost every organization does this, and they’ve probably been doing it since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution.

I get it, but setting single-number KPI targets causes some surprisingly serious problems that, I think, are obvious when they’re pointed out, and I think a better approach exists.

What, exactly, is wrong with single-number KPI targets?

Scenario time…

At the beginning of this quarter, our company’s CEO set a sales target of $5M for the quarter, but we ended up just missing it and we only hit $4.96M. So, how should we feel about $4.96M? It seems kind of silly to feel that we “failed” when, from the company’s perspective, $4.96M is virtually the same as $5M.

We could instead just say that, for all intents and purposes, we hit the target, but what if we’d hit $4.9M instead of $4.96M? Should we still consider that we “hit the target, for all intents and purposes” at that point? What about $4.8M? $4.5M?

Basically, at what point do we start to consider sales to be a problem that we need to take action on? With a single-value target like $5M, this is left up to the reader to decide, and they may or (much more often) may not have enough background knowledge to determine that.

Worse yet, different readers will have different takes. Some will say that $4.8M is still fine, whereas others will say that $4.8M would be a huge problem that needs to be solved.

And what if we exceeded the target and hit $5.2M? Would that still be "fine," or would it be absolutely amazing? Hmmm…

What's going on?

I think the underlying issue here is that the CEO expressed her expectations of what sales revenue should be as a single number (i.e., $5M), but that’s not how she—or anyone else—actually thinks about sales.

To find out how the CEO actually thinks about sales, we could show her a series of theoretical sales values to react to such as, say, $4.5M, $4.6M, $4.7M […] $5.4M, $5.5M, and ask her what she’d think if sales were at each of those levels. If we ran this exercise, she might tell us something like this:

If sales were below $4.7M, that would be a disaster. We’d have to lay people off.

If sales were at or above $4.9M, that would be fine.

If sales were above $5.2M, that would be more than just fine. We’d probably hire a few more employees at that point.

If sales were above $5.7M, that would be amazing. I doubt we’d ever hit that but, if we did, I’d adjust my expectations upward for future quarters.

Expressing the sales target as a single number like “$5M” doesn’t capture any of this crucial information.

“But,” I hear you collectively say, “we could report the percentage that we’re above or below each KPI’s target instead, and define, say, 5% below target as a problem, and 10% below target as a major problem.”

Sounds good in theory; doesn’t work so great in practice. Why not? The gotcha with this approach is that the same thresholds (e.g., “5% below target is a problem and 10% below target is a major problem”) can’t be applied across all KPIs because being, say, 5% below target would be a catastrophe for some metrics (e.g., “Website Uptime”) and a total nothing burger for others (e.g., “Cash On Hand”).

Therefore, reporting that a given metric is "x% below target" doesn’t actually tell the audience much. Depending on the metric, that could be fine, or it could be a disaster, and it’s entirely up to the audience to figure that out.

Is there another way to set targets that doesn’t have all these downsides? I’m glad I assumed that you asked…

Set four numbers for each KPI

In my Practical Dashboards course, I recommend expressing expectations for the performance of a KPI as four numbers, rather than just one. Each of these four numbers has a very specific definition:

Crisis: The level at which we’d pretty much drop everything until this KPI improved.

Actionably bad: The level at which we wouldn’t just be concerned, we’d be so concerned that we’d do something (e.g., cancel bonuses, launch an investigation, etc.)

Actionably good: The level at which we wouldn’t just be pleased, we’d be so pleased that we’d do something (increase bonuses, make new investments, etc.)

Best case: The best we’d realistically be able to achieve for this KPI. We’d probably never hit this number but, if we ever did, that would be extraordinary.

Using these four numbers, we could represent the CEO’s thoughts about sales revenue accurately, like this: